Benjamin Lillywhite Jr.

Dorothy’s Great Grandfather

Benjamin and Mary Lewis led remarkable lives, and along with so many other pioneers played an important role in the building of a nation. Benjamin was born September 23, 1843. He died December 7, 1939, two years to the day before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He was in his 97th year. Mary Lewis was born July 27, 1845. She died January 24, 1914, in her 70th year. The two were married in Beaver, Utah, December 25, 1865.

Benjamin Lillywhite’s original cabin on North Creek, Beaver, Utah.

Rear view of Benjamin’s cabin.

South side view of Benjamin’s cabin.

North side view of Benjamin’s cabin, with cement block addition (1996).

Benjamin Lillywhite was bishop of the Greenville Ward, Beaver Stake in Utah from 1880 to 1885. He was ordained a bishop on April 11, 1880 by John R. Murdock.

Benjamin and Mary Lewis Lillywhite’s home in Beaver, Utah. October 2000.

Document description:“Typescript of a biographical sketch of Benjamin Lillywhite of Brigham City, from an interview…by Kenneth L. Seifert in 1939.” The document consists of four pages.

American Family Portrait

by Herold Stoney Lillywhite

Here is the story of one man and a tenth of his family [son Joseph Lillywhite], and their part in the development of the West. Here, perhaps, is not a typical family, but not a highly unusual one. And here is some of the bone and sinew of America, some of the fiber of the West.

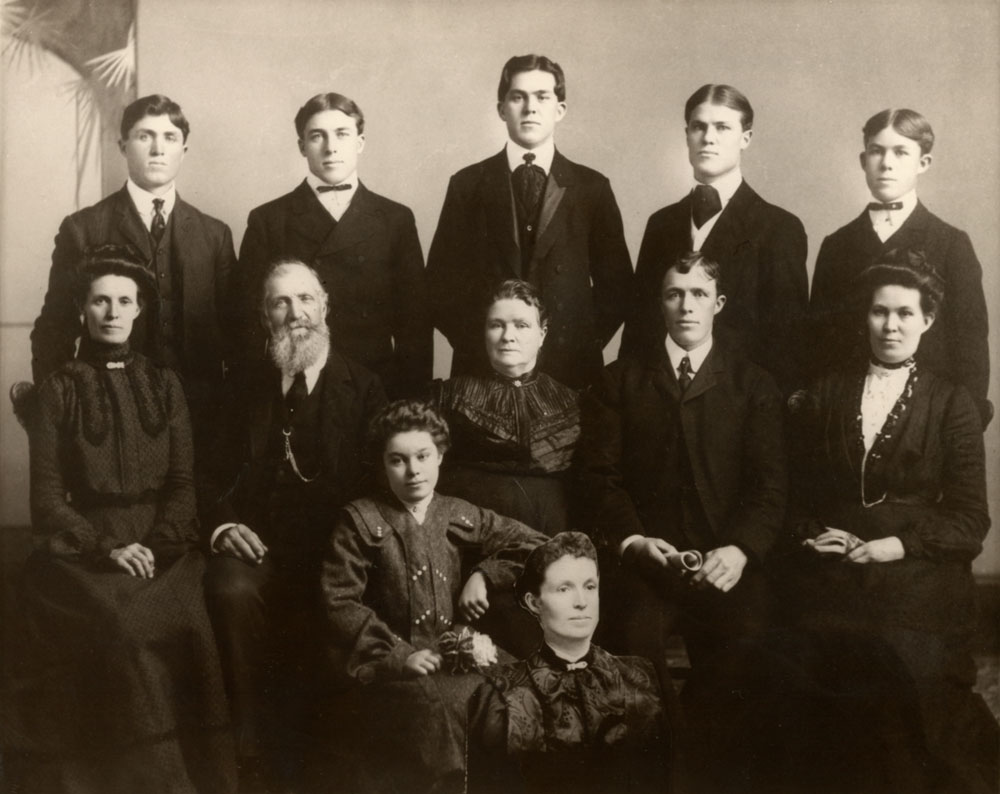

Top row (left to right): Lewis, John, William, Daniel, James. Middle row (left to right): Mary Jane, Father Benjamin Lillywhite, Mother Mary Lewis Lillywhite, Joseph, Isabelle. Front row (left to right): Nellie LaVern. Added to the picture at the bottom: Katherine (oldest daughter).

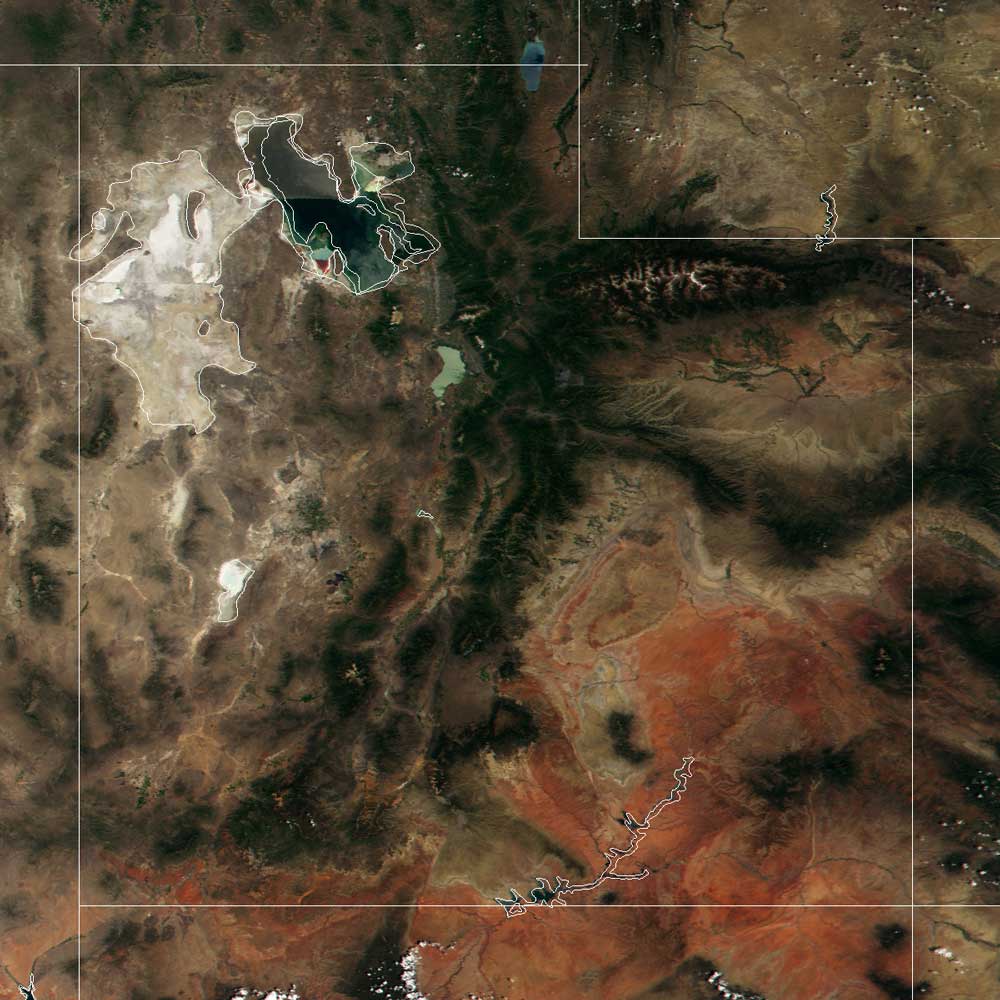

Brigham City, Utah

On the Court House lawn of Brigham City, Utah, Benjamin, now ninety six years old, joined a few other natives of ancient vintage, perhaps twenty years his junior, but less able to navigate than he. He squinted his one good eye at second and third generation neighbors who had come to consider him a permanent fixture on the Court House lawn. He talked a little to a friend about the war raging in Europe, and about the wickedness of the younger generation. Benjamin also talked about not feeling well of late.

After an hour or so Benjamin hobbled the three blocks back to the home of his eldest son Joseph, with whom he had lived for the past several years. As he passed the City Hall he stopped a young man and gave him a brief but vigorous lecture on the evils of the cigarette he was smoking. Benjamin’s Mormon religion taught him that the cigarette is a tool of the devil, and that he must try to protect mankind from it. Then muttering to himself he continued on home.

That afternoon he read a bit from the Book of Mormon, scanned the Church section of the Deseret News, and carefully read the world news on the front page of the local paper. He also listened to the news broadcasts and worried about the war out loud, but to no one in particular. He grumbled whenever there was anyone around to hear him, bewailing the fact that he hadn’t enough money to buy a car so that he could get himself a young wife and go on a trip. For twenty years Benjamin had wanted these two things, a car and a young wife. What did it matter that he had worn out two wives and was almost a century old?

An Honorable Life

The next morning Benjamin said that he did not feel like getting up. Two days later he died quietly. He had gone to the reward he was absolutely certain would be his after a life of righteous living. His belief in a glorious hereafter had been so firm that his last years were spent in eager anticipation of what was in store for him after he died.

The death of Benjamin ended a life that spanned ninety six remarkable years in the making of a state and a nation. It ended a life that had witnessed the settlement of the Great Salt Lake Desert, and the development of Utah.

Benjamin’s family of ten sons and daughters, and numerous grandchildren and great grandchildren, was scattered all over the world. His life was typical of the hardy men that pioneered and developed the United States of America, especially of those who settled Utah and the West. It is fascinating to contemplate the events and changes that took place in Utah during his ninety six years.

Benjamin’s Parents

Sometime in the early 1840s, in London, England, Mormon missionaries converted and baptized Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Lillywhite Sr. The missionaries so fascinated them with tales of “Zion” that the Lillywhites sold all their possessions, and in 1847 bought passage for themselves, their four year old son, Benjamin Jr., and their daughter Sarah age two, on a chartered Mormon immigrant ship to America. They hoped to join the Saints in Nauvoo, Illinois.

Travel to Zion

Early in 1848, the family left New York for St. Louis, Missouri. Mother and daughter traveled the dusty miles in a covered wagon. Five-year-old Benjamin and his father walked beside the wagon during most of those miles. Thus began for Benjamin a life of struggle and hardship, which was to be his lot for almost a century. During the last days of the journey the elder Benjamin contracted cholera, from which he never recovered. He died in June of the following year. Not long after his death the infant Sarah also contracted cholera and died. Benjamin was only nine at the time.

When Benjamin and his mother arrived in St. Louis, they encountered a hotbed of anti-Mormon sentiment. They also learned about the death of Joseph Smith the prophet in Carthage, Illinois, and that the Mormons in Nauvoo were being driven West. It was clear that Zion was no refuge for the destitute Lillywhites. Adding to their difficulties, a boy, later named Joseph, was born to Mrs. Lillywhite in November, only five months after the death of her husband. She couldn’t remain in St. Louis alone with her two sons, so she placed both boys in the care of Latter-day Saint families going out to Utah, while she remained in St. Louis to work until she could finance her way to Salt Lake City. Benjamin was taken to Utah by the Miller family as part of another wagon train. Tragically, Mr. Miller died prematurely on the plains of Iowa. Nine-year-old Benjamin was tasked with driving the ox team the rest of the way to the Salt Lake valley. The family arrived in September 1852.

Mrs. Miller accepted the suggestion of her church leaders to waste no time grieving, or finding another husband. She married Matthew Mansfield later in the year. Benjamin remained with the Mansfields until after he was seventeen.

[Note: Kenneth L. Seifert interviewed Benjamin in 1939. Benjamin indicated to his interviewer that he was released by the Mansfields after reaching his 21st birthday. Apparently it was the Mansfields who gave him a horse and saddle when he was released to join his mother. See the transcript at the bottom of the previous column.]

Miracle of the Gulls

After the persecutions in Nauvoo, Brigham Young turned his face to the West with the comment, “If there is a place on earth nobody wants, that is the place I am hunting for.” In 1852, the Great Salt Lake Desert must have looked to the new arrivals like the place “nobody wants.”

For example, in 1847, the first year the Saints settled in the valley, nearly all the work of the pioneers was destroyed by a heavy frost. Crickets ate what was left, and hunger stalked at every door during the long winter.

The next year crops looked good, and the Mormons looked forward to a winter with enough to eat. One day, late in the summer, a cloud of black crickets appeared devouring the crops like fire. Neither flooding, burning, nor praying seemed to have any effect on the unwanted intruders. Then one day, as suddenly as the crickets had come, a cloud of white seagulls appeared. They fell on the crickets, eating and disgorging them on the spot until the plague was wiped out and some of the crops were saved. The Saints believed that the gulls were sent by God to protect His people. Since that time the seagull is protected in Utah. A seagull monument stands on Temple Square at the corner of Main and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City, Utah.

One Room Cabin

Utah farmers fared a little better over the next three years. By the time Benjamin entered the valley late in the summer of 1852, the crops were doing well, and there was a promise of food for winter. The Mansfield family was apportioned a small plot of land outside the settlement area. Inside they set about building a log cabin on one of the city’s well laid out blocks, with logs Benjamin helped his foster father cut and haul from City Creek Canyon. The cabin had a dirt floor with only one window covered with an animal hide. The door was so small that even nine-year-old Benjamin had to stoop to get through it. The Utah Territory had been organized by Congress only two years before in 1850. Thus the young Benjamin helped build a new home in what was becoming an integral part of a great nation.

City Creek Canyon looking south over the Salt Lake Valley.

Trial of Faith

When Church leaders called families to colonize different parts of the territory, it often meant starting life over as a sore test of religious faith. In 1853, the Mansfields answered the call to join a new colony in Millcreek, a short distance south and east of Salt Lake City. The first settlers of the Millcreek area included Mary Fielding Smith (widow of Hyrum Smith) and her children, including Joseph F. Smith, sixth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Benjamin worked like a man building a shelter and planting crops in the new area. He was still a boy, however, and missed his mother and brother in St. Louis as only a boy his age could.

Indian Troubles

Benjamin got his first taste of Indian fighting in 1854. The Walker War was a series of skirmishes between the Mormons and the Ute Indians between July 17, 1853 and July 27, 1854. After Briahm Young directed the people to build centralized forts for protection, the Mansfields and Benjamin worked along side others to finish a stockade before an attack. When it came they were ready. Millcreek was saved, with most of it’s stock and food. In later years, and despite this beginning, Benjamin became a great friend of the Indians and a peacemaker between them and the settlers.

Hard Times

In 1854, Benjamin helped his foster-family fight another grasshopper infestation that destroyed crops, and raised the specter of another winter without food. In 1855, crops were again destroyed by grasshoppers, and settlers lived through the year by the barest margin. In 1856, a drought added to the settlers problems. Benjamin lived on anything edible that could he gathered from the hills. The Tintic War broke out between the Indians and the settlers in the Tintic and Cedar Valleys 50 miles south-southeast of Salt Lake City. The Indians, displaced by settlers establishing mining communities in the area, were stealing cattle because of the drought. Mr. Mansfield was called away from his farm for several months to help the volunteers from other settlements. The burden of the farm fell on young Benjamin’s shoulders.

Handcart Companies

In 1856, handcart companies began migrating across the plains to Utah. Early snows caught the Willie and Martin handcart companies along the Sweetwater River in Wyoming and many perished. It’s not likely Benjamin was in the meeting when Brigham Young called for a rescue effort, but he certainly would have known about the prophet’s famous plea: “Many of our brethren and sisters are on the plains with hand-carts, … and they must be brought here. … Go and bring in those people now on the plains, and attend strictly to those things which we call temporal, … otherwise your faith will be in vain.” (Deseret News, Oct. 15, 1856, 252.)

Margaret Mitchell Lillywhite

After arriving in Utah, Margaret began the search for Benjamin and Joseph. When she found Benjamin, Mrs. Miller (now Mansfield) and Mr. Mansfield persuaded her to leave Benjamin with them. Not only had they become attached to him, but he was old enough to help repay them for the years of care and protection they provided.

With more difficulty she located Joseph, and was able to take him without protest from the family. As soon as Joseph was old enough, he worked to support himself and his mother.

Margaret married several times as a plural wife. After the death of John Eldridge in Fillmore, Utah, Joseph and his mother were left alone and hungry. Friends advised them to move to Beaver where Joseph found work on a dairy farm. Not long after Joseph and his mother arrived in Beaver, Benjamin told his foster parents goodbye in Millcreek, mounted the horse that he had somehow acquired, and headed south. He reached Beaver late in 1860, traded his horse for forty acres of land and squatter’s rights at North Creek, and set to work once more to build a log cabin. He was again near his mother and brother, but he never did live with them.

The Stoney Family

The same year that the Lillywhites went to Beaver, Robert Stoney, of Leeds, England, and his wife, Sarah Jaheman Stoney, of Sheffield, arrived with an infant daughter, Sarah Ann, in New York City aboard a Mormon immigrant vessel with a group of other Mormon converts, after six terrible weeks on the North Atlantic. They made their way to Florence, Nebraska, and there began the trip across the plains with a handcart company. Robert Stoney pulled the handcart all the way, but his health was broken from dust in his lungs. He had heen a needle-maker in Leeds. His wife pushed on the cart from behind and often carried the baby in her apron, holding the comers of it in her teeth to leave her hands free for pushing. They made the crossing to Salt Lake in 1860, and in the summer of 1863 moved south to settle permanently in Beaver, Utah. Robert and Benjamin became life-long friends, and two of their children Joseph Harvey Lillywhite and Elizabeth Ellen Stoney eventually married.

Margaret Lewis

In 1863, the Lewis family came to Beaver from South Wales. They had a pretty, black-eyed daughter named Mary. She was 18 at the time. Benjamin, who was 20, met and fell in love with Mary Lewis. They were married December 25, 1865, in the church Endowment House “for time and eternity.”

A short time later Benjamin’s mother married again, to a Mr. Elijah Elmer, a farmer living south of Beaver.

Black Hawk War (1865-72)

Late in the Fall of 1865, the Black Hawk War broke out. Benjamin was a member of a volunteer army called “Minute Men” who pledged to protect white settlers from the rampaging Indians. Benjamin served in Company Two under Captain Joseph Betterson. They were stationed at Fort Sanford on the Sevier River. Each company served for thirty days, then went home for thirty days to look after crops and families.

Benjamin learned more about the ways of the Indian, and gained considerable sympathy for them. He also gained a healthy respect for them as warriors. During one of his thirty day leaves, Benjamin returned to Beaver only to find that Mary was having a difficult time running the farm alone, and that Ute Indians were a constant threat to the settlers there. He also learned that Joseph was at that moment lying critically wounded from a bullet fired by a raiding Indian.

Lee’s Ranch Indian Raid

Joseph had worked for some years on a dairy farm ten miles south of Beaver on Birch Creek. The farm was owned by Punkin Lee, brother of John D. Lee of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. One morning just after dawn, Joseph opened the door of the Lee cabin to go to the barn. As he stepped outside a shot rang out and he fell to the ground with a bullet through his shoulder. Immediately the woods surrounding the cabin burst into a frenzy of gunfire mixed with wild shouts from Ute Indian raiders. Joseph managed to get back into the house before he collapsed from loss of blood.

The Indians closed in on the house shooting wildly at doors and windows. They tried to set fire to the house, but shots from the men inside prevented it. After some hours of fighting the situation looked hopeless. In desperation the men took an almost unbelievahle chance. Two of Lee’s children, Rueben twelve, and Rose eight, were put through a back window of the cabin with instructions to get help in Beaver ten miles away. By some miracle the children alluded the Indians and headed for Beaver. Soon Rose could go no farther, so Ruehen concealed her in a clump of sagebrush before going on. In Beaver the exhausted boy found most of the men working on the new church house. They were already armed and ready to ride as a precaution against Indian attack. Thus prepared, they were off to the rescue with the courageous Rueben on a horse behind one of the men. On the way they stopped and got the frightened Rose, still crouched, almost paralyzed with fear, in the clump of sagebrush.

The battle at Lee’s Ranch became critical. The Indians threw a lighted torch through a window, which caught fire on the curtains and rug carpets. There was no water in the house, and no one could get to the well outside. Mrs. Lee came to the rescue with pans of milk set out in the corner of the room from the milking the night before, which saved the house from fire. Just then the men from Beaver arrived and drove the Indians off. It was also none to soon to save the life of Joseph, who had been bleeding throughout the day. Although he recovered from his wound, it contributed to an early death.

The Next Generation

In January 1867, Mary Lewis Lillywhite gave birth to her first child, a daughter, named Catherine. Later the same year the Salt Lake Tabernacle was completed, grasshoppers infested the settler’s crops, and Benjamin returned home from the Black Hawk War. Benjamin came from trouhle with the Indians to a different hind of trouble at home. He found the once peaceful village of Beaver now turned into a crawling camp of miners, who rode rough shod over the Mormon settlers. The early settlers had paid little attention to the arid mountains west of Beaver, but outsiders had dug in them and found “riches”, which the Mormons promptly labeled “coins of the devil.” There was a brief boom and prosperity for business in Beaver, but there was also misery and mistreatment, suspicion and hatred for the farmers and their families. Lust and licentiousness erupted the peace of the little town. The drunken miners paid no attention to decencies, and any woman was considered fair game, especially if she were a daughter or wife of the hated Mormons.

Benjamin’s attention was on his forty acres west of Beaver, and his pretty wife and daughter. He set to work to make a family living. Not long after his return from the war he landed a job as mail clerk for the government. His task was to deliver mail by ox or horse team between Fillmore and Cedar City. This was a long and hazardous route, always subject to Indian raids. It was during this period that Benjamin won the respect and protection of the Indians, whose farm became a haven for many of them. In winter they would pitch tents on his farm and then trade him buckskins and other goods for food. They came to him to settle their troubles and heal their sick. He became their friend because he learned to speak their language and to sympathize with their problems. As a consequence, he never lost a pound of mail or freight in all his years on the road.

In 1869, a second daughter, Isabelle, was born to Benjamin and Mary. The mining boom in Beaver was coming to an end as the ore began to play out. In Salt Lake City, a U.S. Land office was opened, making it possible for Utahns to get titles to their land. After Benjamin bought forty acres next to his first forty, his farm was one of the finest in the area.

Benjamin’s Brother Joseph

After Joseph married in 1869, he was called almost immediately to help establish a colony in Old Mexico. He went, and never again saw Benjamin or his mother Margaret. After he and his family were driven out of Mexico in one of its numerous revolutions, they settled in Arizona’s Salt River Valley (Phoenix Metropolitan area). Joseph died a few years later from the bullet wound he received in his youth at Lee’s Ranch.

Benjamin Prospers

Benjamin and Mary worked hard and prospered. He was beginning to be recognized as a leader in the Church, and valuable community agent in helping to make peace with the Indians. He was also recognized as a friend and a man who could keep his word.

The social life of Beaver was never dull, and Benjamin and Mary took part as much as their time and growing family would allow. Benjamin became a member of the famous Beaver choir and brass band, and Mary took part in the newly organized Beaver Dramatic Society. All of it was under the direction of Robert Stoney. In January 1872, Mary Lillywhite gave birth to twins. Only one lived. He was named Joseph Henry in a priesthood baby blessing, which he received a little later in church.

A year and three months after the birth of Joseph Henry, a daughter was born to Robert and Sarah Stoney. She was the sixth child in what eventually become a family of ten. She was blessed Elizabeth Ellen in the same church where Joseph Henry received his name and blessing. Destiny linked these two families together when Joseph Henry and Elizabeth Ellen married years later.

The United Order

In 1872, several other important events took place. The first street car system opened in Salt Lake City; the war over polygamy raged with increasing fury in and out of the Territory; and talk of the United Order became common, which Brigham Young formally introduced two years later.

In 1874, Benjamin had a hard time bringing himself to join the United Order as organized. This was a “regionwide economic plan aimed at placing production and distribution under community-owned cooperatives. Though almost every ward organized an order, the plan had an important economic effect in only a few localities.” [See Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Social and Cultural History, and United Orders.] All goods were to he voluntarily turned in to a central storehouse from which food and clothing and other necessities were dispensed to all according to need. Men were given credit for the amount of goods they turned in, but it was difficult for many to see any other benefit. Each man worked his land or pursued his trade for the good of the community, not for his own enrichment. Benjamin had made a good start with his homestead, and it was not in his nature to give it up easily. His friend, Robert Stoney, readily accepted the idea and urged Benjamin to do likewise. In the end, both Robert and Benjamin gave up all they had and joined the United Order. They retained the title to their lands, however, so the farm was not lost to Benjamin.

Also in 1874, John D. Lee was brought to Beaver to stand trial for his part in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The trial lasted two years, during which time church members learned more about the facts in the case. Lee was found guilty and later shot at the scene of the crime, where he fell backward into his coffin. Officially Lee’s conviction ended the matter. It would be years before the details were made public.

St. George Temple Dedication

In 1877, Robert Stoney’s choir and his Beaver brass band made Utah history. After the St. George Temple was completed in the “Dixie Mission,” Brigham Young went down from Salt Lake to dedicate it in one of the most elaborate celebrations the Church had known.

Robert Stoney’s choir and band were brought from Beaver to St. George to furnish music for the occasion. Benjamin Lillywhite drove his team and wagon to take a load of singers to the dedication. At sunrise on April 6, 1877, Robert led his band as it played the Star Spangled Banner from the top of the St. George Temple. Brigham Young and many of the apostles stood below among the proud Mormons who had built the Temple. Later in the day the Beaver choir, led by Robert, and with Benjamin among the singers, won warm words of praise from President Young and other speakers.

After the dedication, Brigham Young returned to Salt Lake City, where be became ill and died, bringing grief to his people. His death represented an immense personal loss to every Mormon in the Territory.

During the next ten years Benjamin became a Mormon Bishop and a civic leader. He continued to prosper, and his family grew at the rate of a son or a daughter every two years. Robert Stoney became more active with his music and other church activities (he was appointed clerk of his stake).

In 1877, the National Congress passed the drastic Edmunds-Tucker Act that finally doomed polygamy and began the confiscation of church property by the Federal government. At the same time John Taylor died as President of the Mormon Church. He was succeeded by Wilford Woodruff.

Margaret Mitchell Lillywhite Dies

—Benjamin’s Mother

In 1879, Margaret Mitchell Elmer, mother of Benjamin and Joseph Lillywhite, and of Horace, Elijah, and Sarah Elmer, died in Beaver at the age of sixty-six. Read more about Margaret Mitchell here.

Utah Politics

The following year the liberals carried Salt Lake City for the first time in an election; Wilford Woodruff issued a manifesto advising church members to refrain from polygamy; a free public school system was established throughout the territoryp; the population of Utah grew to 210,779 (including 12 Lillywhite’s and 12 Stoney’s), and Benjamin and Mary’s ninth child was born.

In 1891, Benjamin declared himself a member of the newly created Democratic party in Utah in opposition to the Republican party. The heretofore active Mormon People’s party was dissolved. The next year Benjamin cast his first Democratic vote, and lectured his twenty-year-old son, Joseph, on the evils of the newly created Republican party.

In 1893, President Benjamin Harrison issued a manifesto of amnesty to Mormon polygamists, the National Congress authorized the return of confiscated property to Mormon Church members, and the Mormon Temple in Salt Lake was dedicated.

The Lillywhite dynasty was still growing. Benjamin was father of ten living sons and daughters, and in December of that year be became the grandfather of the first son born to Joseph Henry and Elizabeth Ellen. This infant, the first of ten, was blessed in the same church in Beaver as his father and mother. He was blessed Joseph Clinton.

Utah Territory Becomes a State

By 1895, the Utah Territory was getting ready for statehood. On May 8th, the Utah Constitutional Convention signed the document that was submitted to the National Congress with Utah’s final petition for statehood. The same month another Lillywhite made her appearance. She was the second child of Joseph and Elizabeth, named Lucille.

While Elizabeth Ellen and her mother-in-law, Mary, were much concerned with the birth and rearing babies in 1895, Benjamin, Joseph and his five brothers, and other farmers in and around Beaver, were struggling desperately against a terrible crop failure that threatened them all with famine. It was a bleak winter that year, but in 1896, as Utah became the forty-fifth State in the Union and should have been rejoicing, the situation became even more desperate. For the second successive year, crops were wiped out by drought.

Benjamin Moves to Northern Utah

Benjamin heard tales of wonderful farming opportunities in the Snake River Plain of southern Idaho. In early spring 1897, instead of planting in Beaver, he traveled north in search of a better farming climate. Benjamin never reached the Snake River Plain, however. He decided instead to try his luck on the northern border of Utah where gentle hills sweep down into a long valley along the banks of the Bear River. With the unmarried members of his family, he settled in the small town of Riverside in Box Elder County, Utah. A short time later, Joseph and Elizabeth moved to Riverside with their three children.

Robert Stoney had decided to weather the drought in Beaver. Four years later, in 1901, he died, the father of ten living children and grandfather of many. In 1907, Sarah Stoney followed her husband in death to the reward she had earned.

Mary Lewis Lillywhite Dies

—Benjamin’s Wife

Benjamin and Mary lived in Brigham City, Utah for a few years. It had been a hard life for Mary, and she was tired. In 1914, she died at the start of World War I, leaving Benjamin so completely alone that he seemed unable to adjust to life without her. Benjamin’s life seemed to stop with the death of Mary. He went through the motions of living, but be longed to be with her on the other side.

For a time Benjamin tried to live alone, but his life was terribly empty. He went to work in the Salt Lake Temple, where he found a second wife. They were married, but it took only a few years to find out that they were too old and too helpless to be of any assistance to each other. She was older than Benjamin, and much more of a cripple than he. They finally parted, each going to live with their children.

When World War I broke out, only one of Benjamin’s six sons was young enough to enlist. Jim became a champion boxer in the Marines overseas, but returned after the war with his lungs and stomach gassed beyond repair. Only one of Joseph’s sons was old enough to go to war. Clinton became an officer in the cavalry and saw first hand the horrors of war.

Elizabeth Stoney Lillywhite Dies

—Benjamin’s Daughter-in-law

In 1923, the talented and beautiful Elizabeth Stoney Lillywhite died. Joseph was even more lost than his father at the death of Mary. He lived in a state of emotional upheaval for several years. Later he met and married a women who could speak only a few words of English, but who was shrewd, honest, big-hearted and lonely. She was a Mormon convert, brought from Germany by a Mormon missionary, Joseph’s brother John. This woman, Marie, wanted a home and Joseph wanted help and companionship. It was a good marriage for hoth.

Benjamin’s Final Days

After the death of Elizabeth, Joseph rented his farm and moved back to Brigham City on East Forest street, where Benjamin came to live with him and Marie in 1933. There Benjamin found comfort and loving care from Marie, and he spent lazy years reflecting on almost a century living in Utah, and of a glorious eternity where he would again be with his beloved Mary. And it was there in 1939, that the prolific Benjamin came home from his walk down to the Court House lawn, went to bed and two days later died quietly.