Benjamin Lillywhite Jr.

Dorothy’s Great Grandfather

Benjamin Lillywhite’s original cabin on North Creek, Beaver, Utah.

Rear view of Benjamin’s cabin.

South side view of Benjamin’s cabin.

North side view of Benjamin’s cabin, with cement block addition (1996).

Benjamin Lillywhite was bishop of the Greenville Ward, Beaver Stake in Utah from 1880 to 1885. He was ordained a bishop on April 11, 1880 by John R. Murdock.

Benjamin and Marry Lewis Lillywhite’s home in Beaver, Utah. They probably moved here from Greenville, Utah.

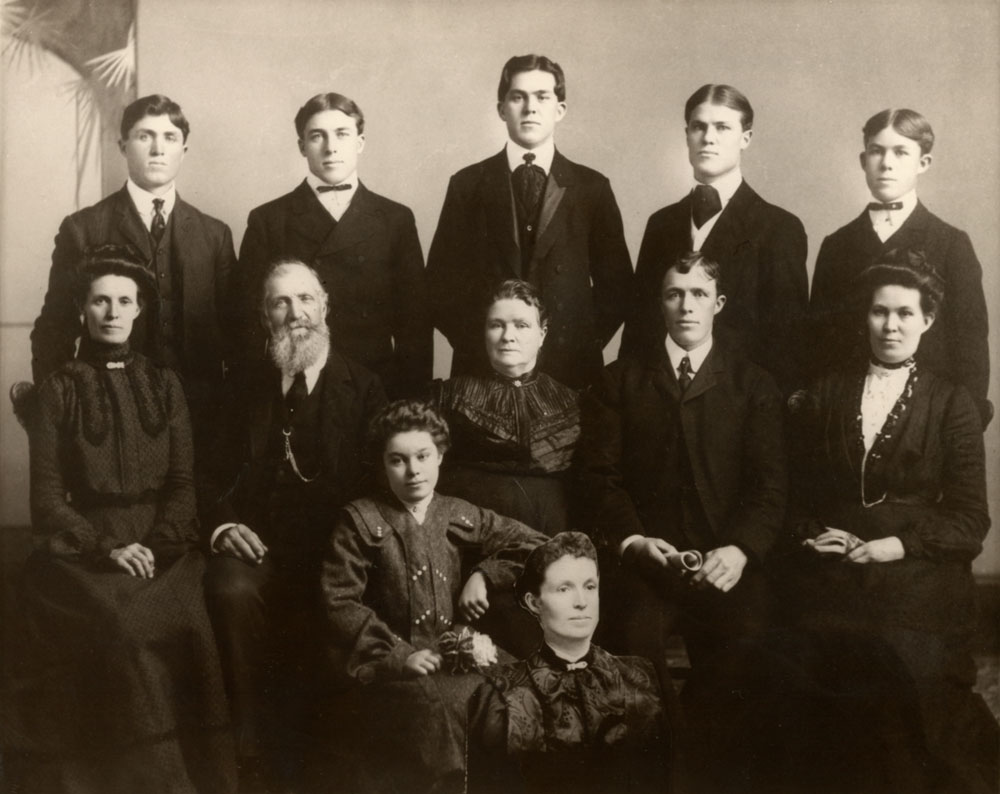

Top row (left to right): Lewis, John, William, Daniel, James. Middle row (left to right): Mary Jane, Father Benjamin Lillywhite, Mother Mary Lewis Lillywhite, Joseph, Isabelle. Front row (left to right): Nellie LaVern. Added to the picture at the bottom: Katherine (oldest daughter).

American Family Portrait

by Herold Stoney Lillywhite

Benjamin and Mary Lewis led remarkable lives, and along with so many other pioneers, played an important role in the building of a nation. Benjamin was born September 23, 1843. He died December 7, 1939, two years to the day before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He was in his 97th year. Mary Lewis was born July 27, 1845. She died January 24, 1914, in her 70th year. The two were married in Beaver, Utah, December 25, 1866.

Benjamin and Mary Lewis led remarkable lives, and along with so many other pioneers, played an important role in the building of a nation. Benjamin was born September 23, 1843. He died December 7, 1939, two years to the day before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He was in his 97th year. Mary Lewis was born July 27, 1845. She died January 24, 1914, in her 70th year. The two were married in Beaver, Utah, December 25, 1866.

Here is the story of one man and a tenth of his family [son Joseph Lillywhite], and their part in the development of the West. Here, perhaps, is not a typical family, but not a highly unusual one. And here is some of the bone and sinew of America, some of the fiber of the West.

The story does not begin or end on a beautiful autumn day in 1939 in Brigham City, Utah, when Benjamin Lillywhite hobbled, rather spryly considering his ninety six years, along the sidewalk down East Forest street to a bench on the Court House lawn. But that date and that place put the story in its natural setting.

Final Days

On the Court House lawn Benjamin joined a few other natives of ancient vintage, perhaps twenty years his junior, but less able to navigate than he. He squinted his one good eye, the one that had served him for almost seventy years, at the sleepy life of Brigham City and at second and third generation neighbors who had come to consider him a familiar and permanent landmark on the Court House lawn. He talked a little in a thin voice to a friend, who could hear no better than Benjamin could, about the war and the wickedness of the younger generation and the fact that he had not been feeling so well of late.

After an hour or so he hobbled back toward the home of his eldest son, Joseph, with whom he had lived for the past several years, three blocks east of Forest street. As he passed the City Hall Benjamin stopped a young man and gave him a brief but vigorous lecture on the evils of the cigarette that the young man was smoking. Benjamin’s Mormon religion had told him that the cigarette is a tool of the devil, and he must try to protect mankind from it. Then muttering to himself he continued on home.

That afternoon he read a hit from the Book of Mormon, scanned the church section of the Deseret News, and carefully read all the world news on the front page of the local paper, mumbling to himself as he repeated half aloud each word that he read. He listened to all the news broadcasts and worried about the war out loud, to no one in particular. He grumbled whenever there was anyone around to hear him, bewailing the fact that he hadn’t enough money to buy a car so that he could get himself a young wife and go on a trip. For twenty years Benjamin had wanted these two things, a car and a young wife. What did it matter that he had worn out two wives and was almost a century old? But, for almost ten years he had to content himself with some such daily routine as described here.

Passing Quietly Away

Next morning Benjamin said he did not feel like getting up. He did not go down town that day. Two days later he died quietly. He had gone to that reward he had been absolutely certain that his life of righteousness would earn for him; the reward that his religion had taught him would be his in after-life. His belief in a glorious hereafter had been so firm that his last years were spent in eager anticipation of what was in store for him after he died.

The death of Benjamin ended a life that had spanned ninety-six remarkable years in the making of a state and nation. It ended a life that had seen the infant settlement of great Salt Lake City develop into the beautiful State of Utah through the strangest history that any commonwealth ever experienced.

Benjamin’s death took away the head of a family of ten sons and daughters, grandchildren and great grandchildren too numerous to account for, and scattered over almost every part of the world. Benjamin’s life was typical of the hardy men that pioneered and developed this nation, especially those who made Utah and the West. It is fascinating to contemplate the events and changes that took place in Utah during his ninety-six years, and the enormous family that spread such hardy stock throughout the country.

Coming to Zion

Sometime in the early 1840’s Mormon Missionaries in London converted and baptized Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Lillywhite Sr., and so fascinated them with tales of the Mormon center of “Zion” in Nauvoo, Illinois that the Lillywhites sold all their possessions and in 1847 bought passage on the chartered Mormon immigrant ship to America for themselves, their four year old son, Benjamin Jr. and their daughter Sarah age two.

Early in 1848 the Lillywhites left New York for St. Louis in a wagon train. Mother and daughter could ride the dusty miles in a lumbering covered wagon, but five year old Benjamin, with his father, walked beside the wagon during most of those weary miles, and thus began for Benjamin, while yet a baby, the life of terrific struggle and almost unbelievable hardship that was to he his for almost a century. During the last days of the journey the elder Benjamin contracted cholera. By the time they reached St. Louis he was so weakened by the disease and the travel, that he never recovered. He died in June of the following year. Soon after this the infant Sarah also contracted cholera and died. So Benjamin Jr. became Benjamin Sr. at the age of nine, and never again did life allow him to he a boy.

The Lillywhites had arrived in St. Louis to find it a hothed of reaction against the Mormons. There for the first time they learned of the murder of Joseph Smith, leader of the Mormon Church, at Carthage. Mormons in Nauvoo were being driven West like leaves whipped before a raging storm. Certainly, there was no refuge there for the destitute Lillywhites. And to add to their difficulties a boy, later named Joseph, was born to Mrs. Lillywhite in November of the same year that her husband and daughter died.

It was impossible for the mother to remain in St. Louis with her two sons, so she arranged to have Joseph taken to Utah with a wagon train, but there was not room for three.

Consequently, Benjamin was adopted by a couple named Miller, under whose care he began the trip to Utah in a different wagon train. On the plains of Iowa Mr. Miller died, and Benjamin now nine, drove the ox team the remainder of the trip to Salt Lake valley, arriving there in September 1852.

Mrs. Miller accepted the practical suggestion of her church leaders to waste no time in grieving or in finding another husband. So, she married Mathew Mansfield late that same year. Benjamin remained with the Mansfields until after he was seventeen.

Miracle of Seagulls

When the Mormons were driven out of Nauvoo, Brigham Young had turned his face to the West with the statement, “if there is a place no one else will have, that is the place I am looking for.” In 1852, “Zion” must have appeared to the new arrivals like the place no one would have. In the first year of its settlement, 1847, nearly all the work of the settlers had been destroyed overnight by a heavy frost, and later what was left was eaten by crickets. Hunger had stalked every door during that long winter. The next year crops had been good until late in the summer. Mormons were looking forward to a winter with enough to eat. But, one day clouds of crickets so black they made the day like night, came out of the sky and fell to devouring the crops like a fire. Neither heating, flooding, burning, nor praying seemed to have any effect on the crickets. Then one day, as suddenly and as mysteriously as the crickets had come, there appeared clouds of large white seagulls from the banks of the Great Salt Lake. These gulls fell upon the crickets, eating and disgorging them on the spot until the plague was wiped out and some of the crops were saved. The legend of the sea gull is one of the greatest in Mormon history. It is firmly believed that the gulls were sent by God to protect His people. Since that time the seagull is protected in Utah, and a great seagull monument stands on Temple Square at the corner of Main and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City.

Utah Territory

The next three years were a little less free from want than had been the previous years, and by the time Benjamin entered the valley late in the summer of 1852, the crops were green with the promise of food for the winter.

After the Mansfields were apportioned a small plot of land some distance from the community center, they set to work to build a log cabin in one of the blocks of the well laid out city. It was the custom of the early Mormon settlers to live close together and to go out around the edges of the settlement to their farms. Here was communal living highly developed and successful.

While Benjamin helped his foster father cut and haul heavy logs from City Creek Canyon and lay them in place for a one room house with one window covered with hide, and a door so small that even the boy had to stoop to get through it to the packed dirt floor within, the National Congress in Washington had finally decided, because of the scare from the quarrel with Mexico, to grant the petition that the Mormon center become a territory. They eliminated the proposed name of Deseret because it came from the Book of Mormon, and substituted the name of Utah, after the Ute Indians. So that year Benjamin helped to build one more cabin in what was beginning to he an integral part of a great nation, the territory of Utah.

Life in Utah

It was the custom of the Mormon Church to “call” certain persons and families to go into different portions of the territory to colonize. Often it was very difficult to leave the comparative comfort that one’s labors had built and go into a barren land to begin anew.

It was a sore test of religious faith. But, in 1853 the Mansfields answered the "call" to go to Millcreek to help establish a new colony there. Millcreek was located only a short distance south and east of Salt Lake City, but at that time it was remote enough to require a new colony. Here once again, Benjamin took the place of a man in building a shelter and planting crops.

Those were desperate years for all in the territory of Utah, but especially were they hard for new colonists. The specter of starvation was always before them during the long winters, and always the never-ending struggle to keep alive in a land that seemed hostile by nature to man.

Benjamin’s mother and brother had not yet arrived from St. Louis, and he was desperately lonely for his family, but at ten Benjamin was a man; he had never been a boy since he had left New York. And now he carried a man’s burdens and felt with a man’s emotions, and always he worked very hard. Life was a never ending battle in this land of outrageous hostility. Everything about Utah seemed to defy man; it’s endless stretches of empty white alkali deserts stretching off into a briny bitter body of water that defied any life within or around it; it’s steep mountains of vicious crags and great canyons, barren for the most part, and at best yielding little in timber for the terrific effort required to get it out. There were hard murderous winters, and long sweltering summers, and always the question of precious water to irrigate the parched land, which would not he broken until it had its fill. Behind all this, there were hosts of living enemies; rattlesnakes, coyotes, bear, wild-cats, grasshoppers, tarantulas, and Indians.

But, there was another side to this wild unbridled land. It was at once a challenge and a blessing Benjamin grew up among a people that had been tempered by a desperate struggle for life; a people who knew what it was to look starvation in the face for long cold months and still carry on. Only intense religious zeal will give men such courage. That is why they were able to conquer the desert. They believed in “faith with works,” and they starved on thistle roots, sego lily bulbs, hawks, owls, crows, and mice, while they clung stubbornly to the land — and conquered it. Even in the midst of such struggles they poured out something of a cry of exultation, a mass hymn of praise for the land with which they were in mortal combat. Many of the religious songs appeared at this time, a number of them in the form of odes to the land in which they lived.

Here is a cry of hope and triumph over an enemy that could he conquered, a land that could he subdued. These people had never been able to conquer their human enemies, their persecutors; they could not conquer blind prejudice, but they could win over this stubborn land. And because they could conquer it they could see beyond it’s fierce cruelty to the wild, outrageous beauty of it’s rugged mountains that thrust their defiant peaks into the everlasting blue of the western skies, where piles of downy clouds tumble about them softening their fierceness and robbing them of their defiance. The very land that refused to he broken until it’s parched spirit was appeased with crystal water from the mountain streams, in the end gave birth to and nourished spreading green carpets of crops, that waved in triumph under the everlasting breezes swept down from the canyons. The hurdle of victory over this hard land was in these people, and the strength and dignity, the rugged simplicity and eternal mystery of the stretching deserts and towering peaks was part of them. This was Benjamin’s land and his people, this his strength and dignity, and his rugged simplicity.

Indian Fighting

It was in 1854 that Benjamin first got his taste of Indian fighting, or rather of protecting himself from the Indians. The “Walker War” was a series of skirmishes between the Mormons and the Ute Indians under the leadership of Chief Wakara (Walker). It came about because the Territorial Legislature of Utah passed a law to prohibit the white slave traffic among the Ute Indians. These fierce red warriors had for years been raiding other Indian tribes, and occasionally white settlements, stealing their women and selling them to the Spaniards in Mexico. In 1853, Chief Wakara, incensed at the Mormon interference, led a raid on Springville, a town about fifty miles from Salt Lake. This was followed by several other fierce raids on other small settlements in that region. As a matter of self-preservation, the Mormon settlements in these parts, hastily built forts in which they could take refuge from such raids. Up on Millcreek the Mansfields and Benjamin worked feverishly to help finish a stockade before an attack should come on them.

When it did come on them, they were ready. Millcreek was saved, with most of it’s stock and food, and Benjamin saw for the first time human beings groveling in the dust in the agonies of death. There must have been something in that first experience with the Indians to touch that serious minded boy deeply, for later he became a great friend of the Indians and a peacemaker between them and the settlers.

In the next ten years Benjamin saw some amazing things happen in and around the territory. Some of these events are difficult to believe even though long since established as fact. While the Mormons wanted nothing except to he left alone to he about their business of making a living from a hostile environment, the outside world would not he content to stop persecuting them even in their mountain isolation. Many incidents occurred to stir the troubled relations. In the same year that the Walker War was settled, a government surveyor by the name of Gunnison was killed with most of his party by Indians in southern Utah. Outsiders blamed the Mormons for setting the Indians upon the party; the charge was later proved untrue, but many believed it anyway. Then the horrible Mountain Meadows massacre, in which 120 of a party of Arkansans, traveling to California, were murdered by Indians, or by Indians and white men dressed as Indians. There has been considerable evidence to indicate that Mormons may have participated in the massacre or even perpetrated it. Only one man was ever brought to justice for it; he was a Mormon Bishop at the time killing took place.

Much sentiment against the Mormons had already been created by the California gold seekers and others passing through Mormon territory. The evidence for the greatest share of their charges is scanty, but some basis in fact has heen found. Certain it is, that the Mormons drove hard bargains with stranded emigrants, and that they dealt harshly with “gentiles” who did not measure up to the Mormon standard of hehavior. There was also much truth in the feeling that all non-Mormons were looked upon by the Mormons with suspicion, and in effect, were considered guilty until proven innocent. It is difficult to see how a group of people that has been so persecuted could have felt otherwise. Be that as it may, there was much fear of the Mormons, and hatred for them, and travelers were told to avoid them at the cost of their lives.

United States Government

Added to all these factors was the Mormons’ natural desire for isolation, their practice of polygamy, their natural distrust of anything “foreign” or “gentile”, and Brigham Young's tendency to oppose the Federal Government’s “interference” in affairs of Utah territory, all serving to bring down the wrath of the government upon the Mormons. In 1847 Brigham Young had said, “give us ten years of peace and we will ask no odds of the United States.” In 1857 President Buchanan ordered General Harney, with a detachment of the U.S. Army, to Utah to put down the Mormon “rebellion.” This rebellion was Brigham Young’s refusal to give up his position as Governor to the newly appointed “foreign” Governor, Alfred Cumming. So ten years after the Prophet had said he would ask no odds of the United States, an army was sent against him, and he made this statement: “We do not want to fight the United States, but if they drive us to it, we shall do the best we can, and I will tell you, as the Lord lives, we shall come off conquerors. We have three year’s provisions on hand, which we will cache, and then take to the mountains and bid defiance to all the powers of the government.”

Hard Times

In 1854, Benjamin had helped his foster-family fight another grasshopper infestation, and had seen the specter of starvation for another winter. The following year almost all crops were destroyed by grasshoppers, and settlers lived through the year by the barest margin. The year after that, famine conditions prevailed through all the territory, and many died of starvation. The lean, wiry, tough Benjamin lived on anything edible that could he gathered from the hills. The same year the Tintic war with the Ute Indians was fought in Utah and Cedar valleys, and Mr. Mansfield was called away from his farm for several months to help the volunteers from other settlements in this war. In this same year, 1856, there was a great “reformation” in the church following a fanatical speech made by Jedediah M. Grant at Kaysville; there followed two years of violently intense religious feeling, persecution by Mormons of all who did not believe, and many rumors of “blood atonement." Before the Territorial Legislature could convene that fall, all of it’s members were taken to the baptismal font to he baptized for the remission of their sins.

And this same year, handcart companies began migrations across the plains of Utah. Early snows caught two of the companies along the Sweetwater river in Wyoming and many perished. Down on Millcreek Benjamin kept alive on thistle greens and owls, and such other items of nourishment.

It had been a most difficult time for Margaret Mitchell Lillywhite since her husband and daughter had died. Not long after coming to the Salt Lake valley, she had received word from a maiden aunt in England asking her to return home to claim a large fortune to which she was the rightful heir. She borrowed money and returned with Joseph to England. Once there she found that the fortune could he hers only upon the condition that she renounce her Mormon religion and remain in England. It was a difficult decision. Margaret Lillywhite had suffered the extreme of poverty. Now she looked at what seemed to be her obligation to her two sons, as opposed to her obligation to her God. But, as she studied over the matter she was surprised to discover that both obligations merged into one; there was no conflict. So she renounced neither her God nor her sons, but her fortune. Once again she and Joseph turned their faces west toward the new land of Zion where they had caught a brief glimpse of the spirit of freedom and the surging progress that blew like a fresh clean breeze across her English background of class privilege and musty prejudice.

So in 1857 Mrs. Lillywhite and Joseph returned to great Salt Lake City. They saw Benjamin shortly, but his mother was too poor to reclaim him, and he was too much grown to come home. Not long after her return Mrs. Lillywhite married Sam Eldridge, a farmer in Salt Lake valley.

Buffalo Bill Cody

When the U.S. Army marched on Utah in 1857, Brigham Young was as good as his word. He sent out guerilla bands under the leadership of the famous old warrior, Lot Smith, to harass the approaching army and destroy it’s supply trains before they reached the mountain barriers east of Utah. How successful they were is shown by an account of Buffalo Bill Cody in his autobiography. He was making his first western trip as a boy engaged to drive cattle for the army. The cattle train was some miles behind the army, about 115 miles east of Salt Lake, when they were stopped. “When we knew that we had fallen into the hands of the Mormon Danites, or destroying angels, the ruffians who perpetrated the dreadful Mountain Meadows massacre of the same year. The leader was Lot Smith, one of the bravest and most determined of the whole crowd. The Mormons stood over us while we loaded a wagon till it sagged with provisions, clothing and blankets. They had taken away every rifle and every pistol we possessed. Ordering us to hike for the east, and informing us that we would he shot down if we attempted to turn back. They watched us depart. We saw the Mormons set fire to the rest of the wagons, which were completely consumed, and for the next few years the Mormons would ride out to the scenes to get the iron that was left in the ashes.”

So effective were the Mormon raiders that General Harney was replaced by General Johnston who gave the army it’s name in history. Johnston temporarily postponed the “invasion” of Utah and wintered with his army and Governor Cumming at Fort Bridger. In the meantime Brigham Young had a dam built in narrow Echo Canyon east of Salt Lake City, by which the whole canyon could he flooded in a very short time if necessary. But, as another precaution he had gathered his followers around him and had begun a migration into southern Utah where he hoped to escape the oncoming army. Preparations had been made to burn the city of Salt Lake to the ground rather than let it fall into the hands of the “foreigners.” The new capitol of the Mormons was a spot near where Parowan is now located. Many of the Mormons reached there and prepared to make it a permanent home. Among them were Sam Eldridge, his wife and Joseph. Later, when many of the Mormons moved back to Salt Lake, the Eldridges stopped in Filmore, a settlement about fifty miles north of Beaver, to make their home.

It was through the good offices of a Philadelphia lawyer, Thomas L. Bane, a friend of the Mormons and a wise man, that peace was finally established between Brigham Young and the government. In the spring of 1858, Alfred Cumming was seated as Governor without any violence, but when Brigham Young and his followers moved back to their abandoned Salt Lake homes, the faithful Mormons still looked to the President of their church for leadership as steadfastly as if the Federal Governor had not been there. That same year Johston’s army moved peacefully into quarters at Camp Floyd in Cedar Valley on the Jordan river.

In 1860, the Pony Express began operations across the continent through Salt Lake, and the National Congress passed a bill outlawing polygamy, which the Mormons refused to recognize. That year also Margaret Eldridge was once more the victim of a relentless fate. Sam Eldridge died in Fillmore, leaving Joseph and his mother again facing hunger. Friends advised them to move to Beaver where there was work for Joseph on a dairy farm. Not long after Joseph and his mother arrived in Beaver, Benjamin sadly told his foster parents goodbye in Millcreek, mounted the horse that he had somehow acquired, and headed south. He reached Beaver late in I860, traded his horse for forty acres of land and squatter’s rights at North Creek, and set to work once more to build a log cabin. He was again near his mother and brother, but he never did live with them.

The same year that the Lillywhites went to Beaver, Robert Stoney, of Leeds, England, and his wife, Sarah Jaheman Stoney, of Sheffield, arrived with an infant daughter, Sarah Ann, in New York City aboard a Mormon immigrant vessel with a group of other Mormon converts, after six terrible weeks on the North Atlantic. They made their way to Florence, Nebraska, and there began the trip across the plains with a handcart company. Robert Stoney pulled the handcart all the way, but his health was broken from dust in his lungs. He had heen a needle-maker in Leeds. His wife pushed on the cart from hehind and often carried the baby in her apron, holding the comers of it in her teeth to leave her hands free for pushing. They made the crossing to Salt Lake in I860, and in the summer of 1863 moved south to settle permanently in Beaver.

Margaret Lewis

There came to Beaver also in 1863 an immigrant family by the name of Lewis, from South Wales. With the Lewises was a dark-eyed, plump, pretty, and exceedingly pleasant daughter named Mary. She was already eighteen, an old maid for those times. Although Benjamin had heen robbed of his youth, and was a sober, serious minded adult, he had not lost a tremendous sparkle and vitality that had always heen his, and he certainly had no aversion to pretty girls, although his ripe old age of twenty might suggest that he was a bit slow in getting started. So Benjamin met and fell in love with Mary Lewis. They were married on Christmas day of 1865 in the church endowment house in a ceremony which, in the eyes of the Mormons, makes the union a solemn and sacred contract everlasting. It ensures it for “time and eternity.”

A short time later Benjamin’s mother also married again; this time her hushand was Elijah Elmer, a farmer living south of Beaver.

That same year the Congregationalists established the first non-Mormon church in Utah and shocked the Mormons into a realization that they were no longer alone. Then late in the fall the Ute Black Hawk war broke out. This was an uprising of the Ute Indians in Eastern Utah. Almost before he knew he was married, Benjamin found himself a member of a volunteer army called “Minute Men” and pledged to protect white settlers from the rampaging Utes. Benjamin served in Company Two under Captain Joseph Betterson. They were stationed at Fort Sanford on the Sevier River. Each company in this motley army served alternately for thirty days; then for thirty days they would go home and look after their crops and families while another company took over. It was here that Benjamin learned more ahout the ways of the red men, and gained considerahle sympathy for them, though he had a healthy respect for their potentialities for mischief when on the war path. During one of his thirty day leaves, Benjamin returned to Beaver to find that his wife, Mary was not having an easy time to keep his forty acres running, that the Utes were a constant menace to settlers right here at home, and that his brother, Joseph, was at that moment lying critically ill from a bullet wound fired by a raiding Indian.

Lee Ranch Indian Raid

Joseph had worked for some years on the dairy farm on Birch Creek, ten miles south of Beaver. This farm was owned by Punkin Lee, brother of John D. Lee of the Mountain Meadows massacre. One morning just at dawn, Joseph opened the door of the Lee cahin to go to the barn. As he stepped out of the door a shot rang out and he fell to the ground with a bullet through his shoulder. Immediately the woods surrounding the cabin hurst into a frenzy of gunfire and the wild shouts of Ute Indian raiders. Joseph managed to crawl back into the house before he collapsed from loss of blood.

The Indians closed in on the house shooting wildly at doors and windows. They tried to set fire to the house, but the gun fire from the men inside prevented it. After some hours of fighting the situation looked hopeless to the whites. In desperation they took an almost unhelievahle chance. Two children of the Lee’s, Ruehen twelve, and Rose eight, were put through a back window of the cabin with instructions to try to get to Beaver ten miles away, for help, if they could escape from the Indians. By some miracle they did get through and headed for Beaver. Soon Rose could go no further, so Ruehen concealed her in a clump of sagebrush and went on. In Beaver the exhausted boy found most of the men working on the new church house. They were all armed, as a precaution against Indians, and their horses were tied to the hitching post. So in a short time they were off to the rescue, with the courageous Rueben on a horse behind one of the men. On the way they stopped and got the frightened Rose, still crouched, almost paralyzed from fear, under the clump of brush.

While the rescue party was on its way, the battle at the Lee's became more critical, at one time the Indians threw a lighted torch through a window and it caught fire on the curtains and rug carpets. There was no water in the house, and no one could get to the well outside. This time Mrs. Lee came to the rescue with pans of milk set out in the corner of the room from the last nights milking. The house was saved from fire just at the moment that men from town arrived and drove the Indians off. It was none to soon to save the life of Joseph, who had heen bleeding considerahly throughout the day. But, he did partially recover from his wound. Years later it was the indirect cause of his death.

In January 1867, Mary Lewis Lillywhite gave birth to her first child, a daughter, named Catherine. Later the same year the Salt Lake Tahernacle was completed, grasshoppers made a new onslaught on the crops of the Mormons, and Benjamin Lillywhite returned home from the Ute Blackhawk war, no richer, but much wiser. Benjamin came from trouhle with the Indians to a different hind of trouble at home. He found the once peaceful village of Beaver now turned into a crawling camp of miners, who rode rough shod over the Mormon settlers. The early settlers had paid little attention to the arid mountains west of Beaver, but outsiders had dug in them and found “riches”, which the Mormons promptly labeled “coins of the devil .” There was a brief boom and prosperity for business in Beaver, but there was misery and mistreatment, suspicion and hatred for the farmers and their families. Lust and licentiousness erupted the peace of the little town. The drunken miners paid no attention to decencies, and any woman was considered fair game, especially if she were a daughter or wife of the hated Mormons.

But Benjamin’s attention was on his forty acres west of Beaver, his pretty wife, and their daughter, rather than upon the wickedness of the miners. He set to work energetically to make a living for them all. Not long after his return from the “war" he landed a job as mail clerk for the government, his task being to deliver mail by ox or horse team, between Fillmore and Cedar City. This was a long and hazardous route, subject to Indian raids at any time. It was during this period that Benjamin won the respect and protection of the Indians rather than their enmity. His farm became a haven for many of the red men. In winter they would pitch tents on his farm and then trade him buckskins and other goods for food. They came to him to settle their troubles and heal their sick. He became their white friend, because he learned to speak their tongue and to sympathize with their problems. As a consequence, he never lost a pound of mail or freight in all his years on the road.

In 1869 a second daughter, Isabelle, was born to Benjamin and Mary. At the time the mining boom in Beaver slackened considerably as the ore began to play out. In Salt Lake City the U.S. Land office was opened, making it possible for Utahns to get titles to their land. Benjamin bought forty acres next to his first forty. This spot grew into one of the best farms in an excellent farming community. This year also, Benjamin’s brother, Joseph, took a wife, and almost immediately was “called” to help colonize in Old Mexico. He went, and never again did he see Benjamin or his mother, even after he and his family were finally driven out of Mexico, in one of it's numerous revolutions, and settled in Arizona's Salt River Valley.

Benjamin and Mary worked hard and prospered moderately. The serious tall, thin young man was beginning to he recognized as a leader in his church and valuable community agent in making peace with the troublesome Indians. The Indians recognized him as a friend and a man who could keep his word. The social life of Beaver was never dull, and Benjamin and Mary took part as much as their time and growing family would allow. Benjamin became a member of the famous Beaver choir and brass band, and Mary took part in the newly organized Beaver Dramatic Society, all under the direction of Robert Stoney, former Leeds needle-maker, who had just returned from Minersville a short time before, where he had gone to live with his family. Mr. Stoney’s musical accomplishments had become so much favored that a few years previously citizens of Minersville had offered Robert a gift of five acres of cleared land if he would move his family there and organize a church choir. This he had done, but while in Minersville the Stoney’s baby, John, had been ill and it was Mrs. Stoney’s firm belief that if they would return to Beaver the baby would live. So, they moved back to Beaver and the baby’s life was spared.

In January of 1872 twins were born to Mary Lillywhite. One died, but the one that lived was a healthy squalling son, later taken to church, given a blessing and christened Joseph Henry.

A year and three months after the birth of Joseph Henry, a daughter was born to Robert and Sarah Stoney, the sixth child in what eventually become a family of ten. She was named Elizabeth Ellen, blessed and christened in the same church as Joseph Henry had been. Destiny had already linked these two together.

In 1872 several other portentous events also took place. The first street car system opened in Salt Lake City. The war over polygamy raged with increasing fury in and out of the territory, and talk of the United Order of Enoch was rife. The territory was undergoing growing pains and the strange Mormon beliefs were once more being tested.

It was difficult in 1874 for Benjamin to bring himself to join the United Order of Enoch that Brigham Young had ordered “throughout the territory.” This was a plan of communal living so advanced that other societies had not dared even to think of it up to that time. All goods were to he voluntarily turned in to a central storehouse from which food and clothing and other necessities were dispensed to all according to need. Men were given credit for the amount of goods they turned in, but it was difficult for many of them to see where there was any other benefit derived. Each man worked his land or pursued his trade for the good of the community, not for his own enrichment. Benjamin had made a good start with his homestead, and it was not his nature to give it up easily. His friend, Robert Stoney, on the other hand readily accepted the ideas and urged Benjamin to do likewise. It is possible that the difference in the attitudes of the two men came from the fact that Robert was older than Benjamin and owned very little property at that time. But, in the end both Robert and Benjamin gave up all they had and joined the United Order. Men did retain title to their lands so the farm was not lost to Benjamin.

That same year the National Congress passed the Poland bill, designed to further strangle Mormon polygamy. It is probably this series of outside measures against polygamy and the constant pressures generated by them that kept Benjamin and Robert from becoming polygamists, because both men listened fully to the advice of their Church and believed fully in it’s tenets. It is doubtful though, that even this pressure would have kept the vigorous and aggressive Benjamin from acquiring another wife, had it not been for the equal vigor and spirit of Mary, firm as she was in her belief in her religion, she could never bring herself to share her man with another woman, and she stood firm, though she probably looked upon herself as a sinner at times. Robert Stoney very likely considered the economic aspects in addition to outside pressure. But, neither man ever entered into polygamy.

The same year the United Order was begun, John D. Lee was brought to Beaver to stand trial for his part in the Mountain Meadows massacre. The trial lasted two years, during which time church members kept a strict hands off policy or orders from their leaders, and in private did much wondering as to the real facts in the case. Lee was found guilty and later shot at the scene of the crime, where he fell backward into a coffin already built for him. His brother, Punkin Lee, outwardly renounced his brother for his crime, but inwardly he was filled with torment because he felt an injustice had heen done his brother. Officially Lee’s conviction ended the matter. Actually the mystery of it is still unsolved, and probably always shall remain so, unless the Church sees fit to open up it’s records.

It was later the same year that Rose Lee, who had gone for help as a little girl out of the back window with her brother, Ruehen, years ago, was married to a young Beaverite, George H. Sutherland, who later became a member of the Utah State Legislature. That same year the United Order was abandoned as a failure, after the sad admission from President Young that his people were not yet ready for it.

The following year, 1877, Robert Stoney’s choir and his Beaver brass band made Utah history. The St. George Temple was completed in the “Dixie Mission” and Brigham Young went down from Salt Lake to dedicate it in one of the most elaborate celebrations the church bad known. Robert Stoney’s choir and the band were brought all the way from Beaver to St. George to furnish music for the occasion. Benjamin Lillywhite drove his team and wagon to take a load of singers to the dedication. At sunrise on April 6, 1877, Robert led his band as it played the "Star Spangled Banner” from the top of the St. George Temple while Brigham Young and many of his apostles stood below with bared beads among the proud Mormons who bad built the Temple. Later in the day the Beaver choir, led by Robert, and with Benjamin among the singers, won warm words of praise from President Young and other speakers.

Brigham Young Dies

The same year that the St. George Temple was dedicated Utah had its greatest and saddest misfortune. After the Temple dedication, Brigham Young returned to Salt Lake City, where be became ill and died, bringing almost unbelievable grief to his people and losing to the world a great man measured by any standard. That event was taken as an immense personal loss by every Mormon in the territory.

During the next ten years Benjamin became a Mormon Bishop and a civic leader, and continued to prosper moderately, and his family grew at the rate of a son or a daughter every two years. Robert Stoney became more active with his musical work and other church activities, and was appointed clerk of his stake, but be did not prosper greatly. He had a small farm, but be was not cut out for farming; his was much more artistic temperament. It was on his farm that be had a misfortune, peculiarly like that of Benjamin in that be lost the sight of one of his eyes. While plowing one day, Robert bent over the moldboard to scrape some mud off it, and a stalk of stubble stuck in his eye. Foolishly be went on working and did not tahe care of it, even though his daughter, Sarah Ann, who was in the field with him at the time, begged him to go to the house. For six years be wore a patch over the eye and bandaged it constantly, then finally lost the sight of it entirely.

In 1877, the National Congress passed the drastic Edmund-Tucker act that finally doomed polygamy and began the confiscation of church property by the Federal government. At the same time John Taylor died as President of the Mormon Church, and Wilford Woodruff succeeded him.

Margaret Mitchell Dies

Two years later Margaret Mitchell Elner, mother of Benjamin and Joseph Lillywhite, and of Horace, Elijah, and Sarah Elner, died in Beaver at the age of sixty-six.

The following year the liberals carried Salt Lake City for the first time in an election, Wilford Woodruff issued a manifesto advising church members to refrain from polygamy, a free public school system was established throughout the territory, the population of Utah was 210,779 (including 12 Lillywhite’s and 12 Stoney’s), and the ninth child was born to Benjamin and Mary.

In 1891, Benjamin declared himself a member of the newly created Democratic party in Utah in opposition to the new opposition party, the Republican party. The heretofore active Mormon’s People’s party was dissolved. the next year Benjamin cast his first Democratic vote, and lectured his twenty year old son, Joseph, on the evils of the newly created Republican party. But Joseph had more immediate interests. Some years before that time he had set about to woo and win a short, very pretty and talented daughter of Robert Stoney, who bad become a perennial leading lady in the Beaver dramatic society, a member of the choir, and the most popular young lady in those parts. Joseph bad grown up with Elizabeth Ellen Stoney, but be was rather surprised when be learned suddenly what an attractive young lady she bad become. The discovery was made at a dance, where as Joseph was indulging in the most absorbing passion of his life at that time, dancing, be found that Elizabeth was also a remarkable dancer. So it was only natural that he should fall in love with this vivacious, talented, and emotional (she always preferred deep tragedy) leading lady. In the intervening years, while Joseph pursued bis amorous intentions with considerable vigor, Elizabeth Ellen became a school teacher in Beaver. Her accomplished father had given her, along with the little schooling she bad, a much more adequate educational background than was common for girls at that time. It was in July of 1892, that Joseph Henry Lillywhite and Elizabeth Ellen Stoney were married in the Manti Temple, twenty years after they bad both been blessed and christened in the same church in Beaver by their parents, Robert Stoney and his good friend Benjamin.

In 1893, President Benjamin Harrison issued a manifesto of amnesty to Mormon polygamists, the National Congress authorized the return of confiscated property to Mormon church members, the Liberal party in Utab was disbanded, and the Mormon Temple in Salt Lake was dedicated. And the Lillywhite dynasty was still growing. Benjamin was father of ten living sons and daughters, and in December of that year be became the grandfather of the first son born to Joseph and Elizabeth. This infant, the first of ten, was blessed in the same church in Beaver as his father and mother bad been, and be was christened Joseph Clinton.

Utah Achieves Statehood

By 1895, the territory of Utah was getting ready to graduate to the rank of statehood. On May 8th, a constitutional convention signed the Constitution that was to be submitted to the National Congress with the final petition for statehood. And in May of this same year another Lillywhite made her appearance. She was the second child of Joseph and Elizabeth, named Lucille.

Whde Elizabeth Ellen and her mother-in-law, Mary, were much concerned with the birth and rearing babies in 1895, Benjamin, Joseph and bis five brothers, and other farmers in and around Beaver were struggling desperately against a terrible crop failure that threatened them all with famine. It was a bleak winter that year, but in 1896, as Utah became the forty-fifth State in the Union and should have been rejoicing, the situation became even more desperate. For the second successive year, crops were wiped out by drought and there was nothing left to harvest.

Benjamin had heard tales of the wonderful farming opportunities in the Southern Snahe river country of Idaho, so the early spring of 1897 found him on bis way north in search of a more favorable farming climate instead of working his land for planting in Beaver. But Benjamin never reached the Snahe river country. Up near the northern border of Utah, where gentle hills sweep down into a long valley along the banks of the Bear River, Benjamin decided to try bis luck. There in the village of Riverside, he settled with the unmarried members of his family. There also, a short time later, Joseph and Elizabeth and their three children also settled for a time.

Robert Stoney had decided to weather the drought in Beaver. Four years later, in 1901, he died, the father of ten living children and grandfather of many, including four children of Joseph and Elizabeth and theirs. Six years later, Sarah Jaheman Stoney followed her husband to the reward she had earned.

The same year that her father died, Elizabeth with four children now, moved with Joseph to Brigham City to take up fruit farming and fruit peddling. In February of the next year their fifth child was bom and named Myrtle. A short time later that spring, Benjamin and Mary followed their oldest son to settle in Brigham City. It was shortly after this that Benjamin met with an accident peculiarly like that of his friend, Robert Stoney, years ago. While chopping wood one day Benjamin was struck in the eye by a flying chip. In spite of all the care they could give it, a malignant growth developed, from which Benjamin eventually lost the sight of one eye completely.

Mary Lewis Lillywhite Dies

Benjamin and Mary lived in lonely contentment in Brigham City for a few years, but it had been a hard life for Mary Lewis Lillywhite, and she was tired. In 1914, as the gathering thunder of war rumbled toward her native Wales across the Atlantic, she died, leaving Benjamin so completely alone that he seemed unable to adjust to life without her. They had been through so much together that being separated was almost impossible.

Benjamin’s life, except for the physiological processes, almost stopped with the death of Mary. He went through the motions of living, but be longed to be with her on the other side: he to was tired. For a time he tried to live alone, but his life was terribly empty. Then he went to work in that haven for old folks, the Mormon Temple in Salt Lake City. Here he found a woman, some years older than he, whom he thought might be a companion for him. They were married, but it was only a few years before both found that they were too old and too helpless to he of any assistance to each other. She was much more of a cripple than he. So, Benjamin parted from his second wife, and each went to live with their children.

When the First World war came to Utah, only one of Benjamin's six sons was young enough to enter. His youngest boy, Jim, became a champion boxer in the Marines overseas, and returned after the war with his lungs and stomach gassed beyond repair. Only one of Joseph’s sons was old enough to go to war. Clinton became an officer in the cavalry and saw the horror of war overseas. Joseph’s youngest and last child, Iris, was a baby at that time, and the family was living in a huge rambling old stone house on a sixty acre farm out from Brigham City on the “North string.” Five sons and daughters were at home.

In 1923, the talented, pleasant, once beautiful Elizabeth Stoney Lillywhite was also tired, and desperately ill. Life had been so hard for the lovely girl, who had never lost her youth, but who had known little but struggle all her married life. She had never forgotten how to laugh, and her fastidious cleanliness and excellent care of her numerous brood were almost legend. She had instilled into her ten children principles of righteousness, of decency, and courage that could never he lost. And Joseph had helped her all this time. In the early years of their marriage they had been happy and had loved each other deeply, and there was youth and hope in them. But, lately life had become such a struggle for them that there was little time for happiness, and their youth and hope were slipping from them. Elizabeth’s illness increased and gloom settled over the great stone house and its occupants. The end was inevitable. Elizaheth died quietly at Thanksgiving time in 1923, leaving a broken-hearted hushand and a grief-stricken family of ten, who had all come to rely upon her for almost everything that is important in life.

After Elizaheth died Joseph was even more lost than was Benjamin at the death of Mary. He lived in a state of emotional upheaval for several years. His family was completely disorganized, the younger memhers going to live with the married ones. In these depths of despair, Joseph found himself in the clutches of a woman who had her eye on his farm and what little money he might have rather than on his comfort. This creature married him hefore he could recover from his grief. But, the marriage was doomed from the start. Elizaheth was still too much with him. So Joseph was divorced after a short but stormy second marriage. Some years later, when he had recovered his equilibrium, he met and married a women who could speak only a few words of English, but who was shrewd, honest, big-hearted and lonely. She was a Mormon convert, brought from Germany by a Mormon missionary, Joseph's brother John. This woman, Marie, wanted a home and Joseph wanted help and companionship. It was a good marriage for hoth.

After Joseph’s family broke up and he found himself alone, he had rented his farm and moved back to Brigham City on East Forest street, where Benjamin came to live with him and Marie in 1933. There Benjamin found comfort and loving care from Marie, and he spent lazy years dreaming of almost a century of Utah that he had helped to create, and of a glorious eternity where he helieved he could again he with his heloved Mary. And it was there in 1939, that the prolific Benjamin came home from his walk down to the Court House lawn, went to hed and died quietly, leaving his progeny scattered all over Utah and the nation.

There is a strange parallel hetween the life of Benjamin and that of his son, Joseph, but there is almost as strange a parallel between the life of Benjamin and that of Rohert Stoney. The latter had fathered six sons and four daughters. Benjamin had married twice, but all of his children were by his first wife. Joseph had married three times, but all of his chddren were by his first wife. And the deaths of these first wives had affected father and son in much the same way.

It remains to be seen whether Joseph’s life will span the numher of years that his father’s did.

When the second world war engulfed the world in darkness, reaching out to America in 1941, descendants of Benjamin in all parts of the nation were struck by its full force. Though his sons were too old for active service, many of his son’s sons and grandsons were called. One grandson flew the famous "Mormon Metear" to bring destruction to the enemy in Italy. Another, a naval officer and son of Joseph, saw the last of the deadly rocket-bombs of the beaten Nazis fall into the English channel beside his ship, while his brother, also a naval officer, helped to bombard Japan to surrender and aided in putting the occupation forces ashore from his cruiser in the third fleet. Great grandsons too numerous to mention were on Okinawa, Australia, Africa, Italy, France, and in the air above and the water beneath, all helping to free the world from its monstrous folly. But, when the final count was taken after peace came, it was found that kind providence had preserved the lives of all these men and boys to return home and help build a more sane world, a world that Benjamin had struggled ninety-six years to make strong.

But it was in January, 1945, just before the end of the war and on the seventy-third birthday of Benjamin’s oldest son, Joseph, that an event occurred that brings into sharp focus the strength and greatness of the family of Benjamin. To Joseph Henry Lillywhite there came in the mail that day, a large manilla envelope. Inside the envelope he found ten letters, one from each of his sons and daughters, a family circular letter in which each had poured out his feelings, his problems, hopes, ambitions, and family news. From every corner of the nation, and from two oceans came this personal history of a great family, one tenth of the seed of Benjamin. Two brothers wrote of themselves and families from Los Angeles, one from a ranch in Nevada, one from a government office in Washington D.C., four from various places in Utah, one from aboard a cruiser in the Pacific, and another from a tanker in the Atlantic. These ten grandchildren of Benjamin told of the collective lives of twenty-four great-grandchildren, and one great-great-granddaughter. They spoke of the two brothers in the service, of the three sons also in uniform and of the several intended or actual in-laws in foreign lands. There were many things about country and prides in the achievements of each. And through all the letters ran sincerity, dignity, sympathy, and a sense of strength and righteousness that comes from keen minds and courageous hearts, a confidence built upon a foundation of honest simple dignity that have become family tradition. There were many things in each letter, but the crux of each was its expression of devotion to family and country.

And to Joseph Henry Lillywhite, seventy-three year old son of Benjamin, there unfolded as he read the letters, a vision of what makes a great family, a great state, and a great nation.

There was in those letters the personal history of an American Family. And when Joseph, with his wife, Marie, had read this family saga, midst tears and laughter and tremendous heartache and wonderful peace and satisfaction, he was moved to add his benediction. He wrote, in answer to the letter, a prayer of thanks, a blessing and a prophecy all in one:

“My Dear Children: The letters from all of you were the grandest present any person ever received. To tell you how I felt is beyond my power of expression. It took me a long, long time to finish the reading. I would read a few paragraphs and then stop. You know, it is difficult to read through tears. I tried to read aloud, but a lump would come into my throat and I couldn’t utter a sound. Marie tried to read to me, and together we wept and smiled. It was a wonderful feeling.

It was a heart-warming sensation which enveloped me as your words carried me away to a land of pleasant memories, to a paradise island with only Lillywhites as inhabitants. How proud your mother would be to claim you all. From her place of exaltation she must look upon all of you with a glowing satisfaction and sincere appreciation of your love and achievements. Words fail me. I want to say so much to you to express the fullness of my heart, its happiness and satisfaction. But, the only words that seem to come are thanks, thanks, and thanks again. To you I say, live your lives fully, honor and cherish your families. Live true to the Lillywhite tradition the best way you know how. Make plans and follow them. Dream dreams and make your dreams come true. Find true ideals and he willing to die for them. These are the things which will make our family live on into the future, and make all of us, our ancestors, we who now live, and descendants, proud of the name we bear.

And there you have it, the ideals that are the key to the secret of a great family. Here is an American Family, unusually prolific, but morally and physically tough, and mentally keen, the fiber of which this Nation, the West, and Utah were made. This is but a tenth of the family of Benjamin. The serious nine-year old boy, who never was a boy, trudging endless crucifying miles across the dusty plains, carried with him the makings of a great family. Benjamin, perhaps did more than his share to “multiply and replenish the earth”, as did his oldest son, but they left no weak stock, no adulterated blood. The West and Utah gave to Benjamin a simple courage and a dignified strength. These he multiplied a hundred-fold and gave them back to enrich this land that he spent his life to conquer.